Hawaiian Music, Its Origins and Evolution

When the sound of Hawaii comes to mind, one tends to think of the soothing rhythms of the ukulele set to the gentle rustling of waves – background music commonly used in elevators, spas, and tropical-themed occasions. While Hawaiian music is often soothing and rhythmic, it is so much more than good background. Music is the very fabric of Hawaiian culture, its humble beginnings rooted in the origins of its people and its later evolution sparked by the arrival and influence of others. Where there’s people, there’s music, and that’s never been truer in the cultural clash of Hawaii.

One of the curious things about the Hawaiian language is that there is no word that translates to “music”. Yet, traces of its structure link back to pre-contact Hawaii, long before settlers set foot on Hawaii’s shores. Mele, or chanting, was a ritual in ancient Hawaii and a means of preserving their ancestors’ history. These chants, paired with the mimetic dance of hula, expressed emotion, charted family genealogy, or told the larger-than-life mythologies of Maui and Pele. This ritualistic song and dance would be guided by a small orchestra of gourds, stone castanets, feathered rattles, and bamboo sticks. The melody remained firmly in the chants, the vocals, while instruments provided pace and rhythm, laying the foundation for early Hawaiian music.

The first major development came with the arrival of immigrants. Laborers were brought in on steamships who brought with them their music. European missionaries introduced Christian hymns in the late 1700s, but it was the Portuguese and the Spanish who brought guitars. Mexican cowboys, or paniolos, taught Hawaiians how to wrangle cattle and how to play. It was the Portuguese who brought cavaquinho – mini-guitars that served as a precursor to the ukulele.

Hawaiians used the strumming style of the paniolos as a reference rather than a rule, tuning the guitars the way they saw fit. This loosening, or slackening, of the strings gave them a distinct finger-picking style. “Slack-key guitar” was dubbed Hawaii’s back-porch music because locals were initially protective of this new style and only shared it amongst families. By the mid-1800s, slack-key was on everyone’s front porch. This, and the onset of the steel-guitar – sliding a piece of steel along the strings to give that delayed, dreamy quality of a day at the beach – were instrumental in distinguishing Hawaii’s “sound.”

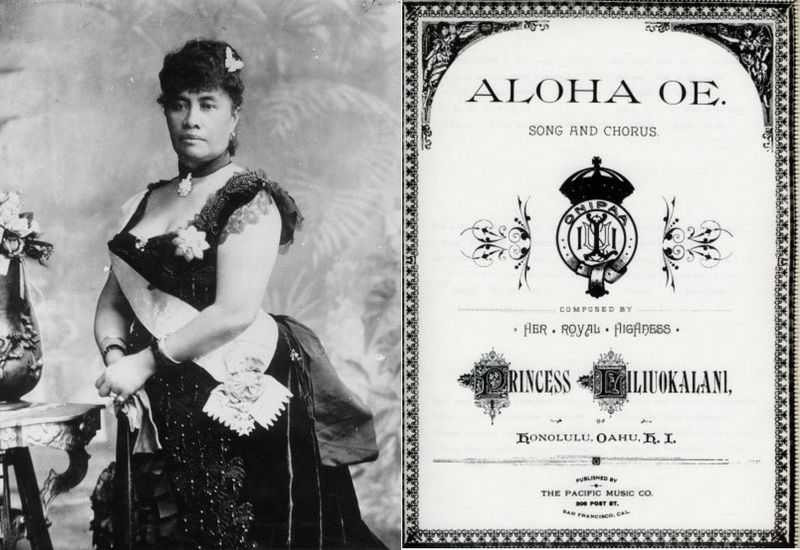

King David Kalakaua saw these innovations as expressions of Hawaiian pride and was inspired to write the state anthem, “Hawaii Pono’i.” His sister Queen Lili’uokalani was also a talented songwriter, writing “Aloha ‘Oe,” and Royal Hawaiian Bandmaster Henry Berger brought both songs to life. In 1915, the Royal Hawaiian Band was invited to compete at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, winning first place. People quickly came flocking to Hawaii’s pavilion at the expo to the tune of “On the Beach at Waikiki.”

Everyone became fascinated with Hawaiian culture. With the advent of recording, people were able to bring Hawaii home with them. A year later in 1916, Hawaiian music sold more recordings on the mainland than any other genre. Bands began regularly touring across America. But it was Tau Moe, a family of four dubbed “The Aloha Four”, who were Hawaii’s first super-group and the first to tour across the world. Demand was now worldwide and Hawaii answered the call in the 1920s with its very own radio program titled, “Hawaii Calls.”

Waikiki became Hawaii’s first major tourist attraction. Hotels began employing bands and dancers to lure crowds. Local radio stations were in a frenzy going from hotel to hotel, setting up equipment to broadcast live. Orchestras that entertained guests were suddenly playing to the world. The radio feverishly became an access point.

Songs began to incorporate English verses or were translated entirely to English to broaden Hawaiian music’s appeal. Hapa haole broadly defined this new subgenre and enabled American artists to pour in with musicians like Bing Crosby, Harry Owens, and Martin Denny. Virtually everyone believed Hawaiians were sitting on the beach and playing the ukulele all day. By 1952, Hawaii Calls was broadcast to over 700 stations.

Hawaiian music inevitably waned in the 1960s with the dawn of Rock. Mainland artists helped grow Hawaiian music, many of whom dipped their toes into the genre purely for style, but promoted an inexplicably tourist-view of Hawaii. The state was doomed to be nothing more than a postcard had it not been for the next era of Hawaiian musicians.

Rock wasn’t necessarily to blame as much as it realigned ideas of what made Hawaiian music so popular. People didn’t want to just visit; they wanted to breathe in the culture and that’s exactly what Gabby Pahinui brought back into the mix. Revered for his slack-key talent and his enchanting falsettos, Gabby found inspiration through jazz. It was his music of choice growing up, an influence that invigorated him as an artist. His innate talent, in turn, reinvigorated the rhythm of the islands.

Gabby was Hawaii’s true renaissance man, ushering in an era of cultural awakening. The Merrie Monarch Festival – once a tourist pageant, became a full-fledged competition as halaus were required to come up with original chants. The challenge was hardly seen as a roadblock, but a license to create. For the better part of the 20th century, Hawaiian music had grown beyond Hawaii’s reach. The artistry and the culture had finally reigned in and gone back to its roots.

Reggae didn’t enter the cultural sphere until the ‘80s where it was met with surprising backlash. Initially a threat to traditionalists, reggae was known for its social critique through the call-to-action lyricism of Bob Marley. The genre echoed sentiments of national pride and anti-colonialism – sentiments shared by many following Hawaii’s statehood in 1959. In many ways, the revival of culture was a reaction to the United States’ overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani decades prior. Music was a way of channeling these unresolved chapters in Hawaiian history. Local groups began expressing these issues in reggae form, leading to the “Jawaiian” subgenre.

The ‘90s brought forth the re-emergence of Hawaiian superstars. Amy Hanaiali’i Gilliom, renowned for her show-stopping falsettos, and Willie K, a guitar virtuoso, fused their talent and enjoyed a fruitful collaboration that saw to their status as the new traditionalists. Keali’i Reichel, with deep ties to the hula community, broke out into the limelight in 1994 with his debut album Kawaipunahele. His blend of contemporary music with traditional Hawaiian chanting struck a chord with audiences, selling half a million copies. Reichel along with The Brothers Cazimero were among the most recognizable names at the Merrie Monarch.

Sonny Chillingworth, Raymond Kane, and Peter Moon were bona fide household names, but the undisputed Hawaiian music star was none other than Israel Kamakawiwo’ole, simply known as Braddah Iz. “Hawaiian Supa’ Man” is the epitome of a popular Hawaiian myth in song form, while his medleys of “Starting All Over Again,” and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” continue to enjoy syndication to this day. Though he died in ’97, his legacy has become the stuff of legend. His debut, Facing Future remains as the best-selling Hawaiian album of all time, etching his myth into Hawaiian music history.

Other genres might have dwarfed Hawaiian music for a time, but the current scene demonstrates a striking flexibility. Local bands often incorporate rock melodies; blues and country artists continue to take inspiration from Hawaii’s rhythmic harmony; and contemporary musicians are beginning to embrace pop elements. If the genre’s perseverance in the last century proved anything, it’s that Hawaiian music is not even close to being history. With artists like Amy Hanaiali’i and Willie K still going strong, and talents like Anuhea and Iration blazing a path, perhaps Hawaii is just getting started.

Featured Artists and Albums

Anuhea ‘Follow Me’

Ekolu – Greatest Hits

Kolohe Kai ‘This is the Life’

Kimie Miner ‘Proud as the Sun’

Iration – Epic Summer Cruisin’

The Green ‘Marching Orders’

Malino ‘From the Start’

Ooklah the Moc ‘Every Posse’

Kolohe Kai ‘Summer to Winter’

Henry Kapono and Friends ‘The Songs of C&K’

Hawaiian Christmas Music

Adrian Manuel is a freelance writer. He’s published articles on Thought Catalog, written a flash piece for A Quiet Courage, and submitted feature essays for The Good Men Project and Mamalode. He also runs an entertainment news blog where he reports on film, television, and music. He lives in Maui.

7 thoughts on “Hawaiian Music, Its Origins and Evolution”

In all the histories of early Hawaiian music and its influence on American mainland music (black & white) there is no mention of WC Handy’s memory of a man in 1903 playing “in the Hawaiian style.” Nor are the amazing guitarists Jim & Bob ever referenced. Why is this?